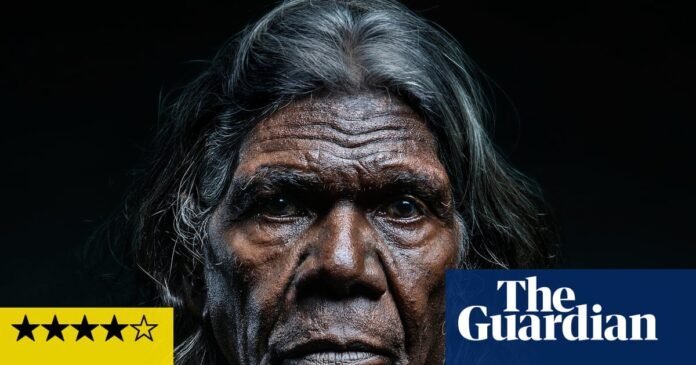

It says something about the eternal qualities of the late and great David Gulpilil that he continues to be at the centre of remarkable stories, even after his death. In Journey Home, David Gulpilil, we learn that the legendary Yolŋu actor – who spent his final years in Murray Bridge, South Australia – had one final wish: to be buried in his homeland of Gupulul in remote East Arnhem Land.

The writer-directors of this elegantly made and culturally illuminating documentary, Maggie Miles and Trisha Morton-Thomas, trace his last journey – a roughly 4,000km trip from, as narrator Hugh Jackman puts it, “a city at the bottom of Australia to a remote swamp at the top”.

Gulpilil’s coffin can be seen in many shots, making him sort of there and sort of not – but his presence can be felt throughout, as if he’s floating in the space between screen and viewer. There’s a lovely visual flourish early on: a shot of a creek overlaid with a monochrome image of Gulpilil in that same waterway, looking delighted. It’s a modest but powerful embellishment that collapses time and space; connecting past and present, folding together the cosmic blanket of existence, and suggesting that perhaps time is not linear but fluid, capable of rippling and reforming like light on water.

That image echoed in my mind throughout the film, which begins in a dreamlike register before pivoting towards a more conventional documentary structure. Miles and Morton-Thomas weave together interviews (including many with Gulpilil’s family), archival footage and scenes of the coffin’s careful transport, each leg of the journey rich with cultural meaning. One thread involves a songline to accompany him “all the way to his grave”; a major element involves the logistical challenges of traversing the country.

The directors don’t get bogged down in details, maintaining a light, airy touch, that gentleness at times smoothing away some of the tension of the effort – for example, when the family’s plans to drive from Ramingining to Gupulul are delayed for months by the arrival of the wet season. In another documentary, this might have been rendered as a moment of high suspense: tight shots, anxious faces, swelling strings. Instead, Miles and Morton-Thomas score it with buoyant, shoulder-swaying music, offering a rhythm that feels celebratory rather than fraught. The film’s stakes are spiritual, not narrative; the mood is cleansing, even buoyant.

Journey Home sustains a soft and meditative tone, its aesthetic textures sun-dappled and dust-specked. There’s nothing corny or overstated in its reverence; the film is gentle without being sentimental, celebratory but infused with melancholy.

It initially surprised me that the directors didn’t integrate more moments from Gulpilil’s films, with these relegated mostly to the opening chapters. This might have deepened the sense of his influence, situating this final journey within the continuum of his onscreen life. On the other hand, it could have given the film a more zeitgeisty feel, potentially taking away from the core elements of the journey. This is not a retrospective; it’s a work about returning to country and, indeed, journeying home.

This film is a fine contribution to an already distinguished suite of documentaries exploring Gulpilil’s life (and death) including Molly Reynolds’s My Name is Gulpilil and Another Country. What sets this one apart is its focus on the collective act of farewell; the way a community carries one of its greatest storytellers back to the country that made his stories possible. It’s a tender and luminous documentary that treats its journey not as an event to be recorded, but an experience to be felt and remembered.