No movie with Imelda Staunton and Bill Nighy can be entirely without interest – and they’re heading up a mighty cast here under the direction of the great Argentinian film-maker Pablo Trapero, making his English-language debut. He has co-written the screenplay with another A-lister: Canadian actor and director Sarah Polley.

And yet the resulting picture, adapted from the 2013 novel by David Gilbert, feels nebulous and laborious. It is dependent on a giant twist-reveal, which is bafflingly implausible and strangely uncompelling even if taken at face value, and which tends to undermine the emotional reality of the whole film and its big confrontation scenes – though there is one riveting showdown between Staunton and Nighy, two black-belts each at the top of their game.

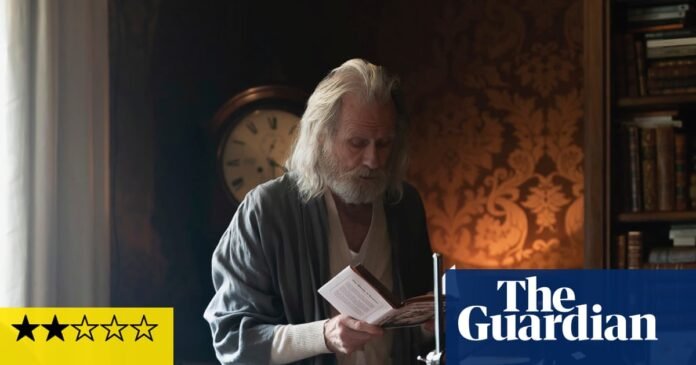

Nighy is Andrew Dyer, a cantankerous old literary lion revered throughout the world for the brilliant novels of his youth, who has published nothing for years and is now marooned like a bearded, drunken hermit in his huge Oxfordshire mansion, boozing, playing jazz LPs too loud and shouting at the walls. He lives with his longsuffering Czech housekeeper Gerde (Anna Geislerová) and high-schooler Andy (Noah Jupe), the product of an affair that destroyed his marriage to Isabel (Imelda Staunton).

Andy is (possibly) like Smerdyakov in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov: the non-canonical brother to his other, older siblings, would-be documentary film-maker Jamie (George MacKay) and recovering alcoholic screenwriter Richard (Johnny Flynn). The entire family is imperiously summoned to the mansion by Dyer.

Andy and Richard are furious with the old man for how he treated their mother but self-hatingly aware they are still using him for their various careers. The film shows that their intense dislike of Dyer is not helped by the extraordinary claim he now makes about Andy – is it just a delusional, self-serving excuse for his infidelity and the only imaginative effort of which the raddled old man is now capable? Or could it be true?

Either way, there isn’t much drama to be had from it. The whole situation circles around Dyer’s revelation without satisfactorily fleshing out its claims to the truth, or its implications as fiction. Jupe, MacKay and Flynn transmit their roles strongly enough, though the male cast are perhaps upstaged by Staunton as Dyer’s estranged wife; it is actually Flynn’s character Richard, furiously obsessed with what Dyer owes him, who delivers the film’s second disclosure, which would be quite enough on its own for most stories.

There are memories here of other films about ageing, conceited toxic-male authors: Bjørn Runge’s The Wife (2017) and Alice Troughton’s The Lesson (2023). Although as a movie about a dysfunctional family, it isn’t anywhere near the quality of Trapero’s own tremendous crime-family movie The Clan from 2015.

& Sons doesn’t deliver on the promise of all its film-making talent but Nighy is always amusing, especially when he crisply orders his nephew Emmett (Arthur Conti) to fix him a whisky. In his untutored way, the kid fills the glass almost to the brim and Dyer grinningly congratulates him on an excellent “Scotch-to-air ratio”.